DEFINITION

Infection control is the protection of patients and healthcare workers by the prevention of infection in the healthcare setting in a cost-efficient manner.

PURPOSE

The purpose of infection control is to reduce the risk of healthcare worker exposure and infection and nosocomial (hospital-acquired) infections, which can complicate existing diseases or injuries.

DESCRIPTION

Organized efforts at infection control began in the United States in the 1950s, along with the increase in intensive care units to care for critically ill patients and the emergence of nonsocomial staphylococcal infections. Many hospitals implemented programs in the 1960s and 1970s at the insistence of various organizations. In the 1980s, state and federal agencies, along with professional organizations, began to make recommendations for infection control and require adherence to regulations.

Infection control procedures are followed in hospitals, long-term care facilities, rehabilitation units, outpatient facilities, and home care. All infection control programs should encourage actions that limit the spread of nosocomial infections. Infection control programs must include the means to measure the effectiveness of procedures, policies, or programs to protect patients and healthcare providers and to determine whether these activities are cost-effective.

Healthcare organizations must be in compliance with regulations and accreditation requirements by various federal and state agencies and governing bodies. The Joint Commission (TJC), a healthcare accrediting organization, has standards that are incorporated into many state licensing, as well as Medicare and Medicaid, regulations. A facility’s administration is responsible for ensuring compliance. Ongoing education and training are an important part of an effective infection control program. Also, the monitoring of patient-care activities can identify areas of concern, and the data obtained is vital to improving the program and ensuring successes.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and its National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases is the focus for information, surveillance, investigation, prevention, and control of nosocomial infections in the United States and around the world. Studies indicate that one-third of nosocomial infections can be prevented by well-organized infection control programs, yet only 6%–9% are actually prevented. The Study of Efficacy of Nosocomial Infection Control (SENIC) carried out by the CDC over ten years showed that, to be effective, nosocomial infection programs must include the following: 1) organized surveillance and control activities, 2) a ratio of one infection control practitioner for every 250 acute care beds, 3) a trained hospital epidemiologist, and 4) a system for reporting surgical wound infection rates back to surgeons (NNIS, 1996).

In 1987, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) expanded previous recommendations to prevent the spread of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and other bloodborne pathogens. Previously, certain isolation precautions were recommended only for those patients who were known or suspected to have bloodborne infectious diseases. Because of the growing number of persons infected with HIV and the high mortality rates associated with AIDS, Universal Blood and Body Fluids Precautions were developed. Under these recommendations, all patients are considered potentially infectious for bloodborne infections. In 1991, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) Bloodborne Pathogen Standard required the use of universal precautions and dictated that all staff must be trained annually on the risk of exposure to bloodborne pathogens. Preventing exposure is the best and safest way to reduce infection.

The effectiveness of infection control programs is evaluated in several ways: lower rates of infection for the patient, shorter periods of hospital stays, decreased morbidity, and reduction of on-the-job exposure of healthcare workers to infection and contamination from patients. To do this, infection control policies focus on strategies for isolation, barrier precautions, case investigation, healthcare worker education, immunization services, and employee health programs. When healthcare institutions are successful in their infection control programs, it decreases the cost of care and has a positive impact on the institution’s image within the community.

It is the responsibility of infection control to identify problems, collect and analyze data, change policies and procedures when necessary, and monitor data. The specific functions of an infection control program should be based on the needs of the individual healthcare institution. It is most important to monitor infection activity. Data is collected and disseminated based on the principles of epidemiology to implement quality-improvement activities and improve patient outcomes. Policies and procedures of the facility must be based on scientific and valid infection control prevention and be reviewed and updated frequently to reflect practice guidelines and standards.

Transmission of infection within a healthcare organization requires three elements: a source of infecting microorganisms, a susceptible host, and a means of transmission for the microorganism. The skin of patients and personnel can function as a reservoir for infectious agents and as a vehicle for transfer of infectious agents to susceptible persons. The microbial flora of the skin consists of resident and transient microorganisms. Resident microorganisms persist and multiply on the skin. Transient microorganisms are contaminants that can survive for only a limited period of time. Most resident microorganisms are found in superficial skin layers, but about 10%-20% inhabit deep epidermal layers. Handwashing with plain soaps is effective in removing many transient microorganisms. Resident microorganisms in the deep layers may not be removed by handwashing with plain soaps, but usually can be killed or inhibited by antimicrobial products. Handwashing is the single most important measure for preventing nosocomial infections.

Handwashing indications

Healthcare workers should wash their hands:

- after removing gloves

- when coming on duty

- when hands are soiled, including after sneezing, coughing, or blowing the nose

- between patient contacts

- before medication preparation

- after personal use of the toilet

- before performing invasive procedures

- before taking care of particularly susceptible patients, such as those who are severely immunocompromised and newborns

- before and after touching wounds

- before and after eating

- after touching inanimate objects that are likely to be contaminated with pathogenic microorganisms, such as urine-measuring devices and secretion collection apparatuses

- after taking care of infected patients or patients who are likely to be colonized with microorganisms of special clinical or epidemiologic significance; for example, bacteria that are resistant to multiple antibiotics

Preparation

Routine hand washing is accomplished by vigorously rubbing together all surfaces of lathered hands followed by thoroughly rinsing under a stream of water. This should take 10-15 seconds to complete. The hands should be dried with a paper towel. Immediate recontamination of the hands by touching sink fixtures may be avoided by using a paper towel to turn off faucets.

Universal precautions recommend that all healthcare workers who come into contact with a patient’s blood or body fluids that contain visible blood should wear an appropriate type of barrier to prevent the spread of blood-borne pathogens. Other body fluids for which barrier protection is recommended include semen, vaginal secretions, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), synovial fluid, pleural fluid, pericardial fluid, and amniotic fluid. The type of exposure determines the specific barrier that should be used. Universal precautions are designed to augment, not replace, standard infection control procedures such as handwashing and the use of gloves when touching obviously infected materials.

Adequate routine cleaning and removal of soil should be the environmental sanitation procedure for all healthcare facilities. Microorganisms are normal contaminants of the environment. A healthcare facility’s environmental services department should maintain schedules for routine cleaning in all rooms and include equipment and working surfaces. General and infectious wastes are disposed of on a regular schedule. All departments are responsible for implementing infection control policies.

COMPLICATIONS

Healthcare workers must not be complacent about implementing their facility’s infection control policies. Perhaps due to long-term exposure to occupationally acquired infections, they have the tendency to minimize or ignore the ramifications. Infections oftentimes go undetected, underreported, or overlooked by healthcare workers.

RESULTS

If infection control programs are successful, the result will be a reduction in the risk of infection and related adverse outcomes in the healthcare setting, achieved in a cost-efficient manner.

HEALTHCARE TEAM ROLES

Much of the responsibility for infection control rests on the shoulders of the clinical staff providing care at the bedside. Because nurses are close to the patient physically, they are able to prevent the spread of infection, but they can also be a means of transmitting infection. Therefore they need to foster compliance with infection control policies to ensure a high quality outcome for the patient. Infection control practices should have a positive effect on not only the clinical staff, but the patient as well.

See also Hospital-acquired infections .

Resources

BOOKS

Damani, Nizam N., ed. Manual of Infection Control and Prevention, 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

McGuire-Wolfe, Christine. Foundations of Infection Control and Prevention. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning, 2018.

Pankhurst, Caroline L., and Wilson A. Coulter. Basic Guide to Infection Prevention and Control in Dentistry, 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2017.

PERIODICALS

Baum, Christina, Michelle Cantu, and Erin Laird. “Lessons in Infection Control: The Role of Local Health Departments in Prevention, Preparedness, and Response.” Public Health Management and Practice 24, no. 4 (July/August 2018): 404–6.

Bearman, Gonzalo, et al. “Hospital Infection Prevention: How Much Can We Prevent and How Hard Should We Try?” Current Infections Disease Reports 21 no. 2 (January 2019).

Sakamoto, Fumie, et al. “Changes in Health Care–Associated Infection Prevention Practices in Japan: Results from 2 National Surveys.” American Journal of Infection Control 41, no. 1 (January 2019): 65–8.

WEBSITES

“Infectious Diseases.” World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/topics/infectious_diseases/en/ (accessed May 6, 2019).

“Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) Infections.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/mrsa/ (accessed May 6, 2019).

“An Ounce of Prevention Keeps the Germs Away: Seven Keys to a Safer Healthier Home.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/ounceofprevention/docs/oop_brochure_eng.pdf (accessed May 6, 2019).

ORGANIZATIONS

American College of Epidemiology, 1500 Sunday Dr., Ste. 102, Raleigh, NC 27607, (919) 861-5573, info@acepidemiology.org, http://www.acepidemiology.org .

American Public Health Association (APHA), 800 I Street NW, Washington, DC 20001-3710, (202) 777-APHA, http://www.apha.org .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 1600 Clifton Rd., Atlanta, GA 30333, (800) 232-4636, cdcinfo@cdc.gov, http://www.cdc.gov

. National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases, 6610 Rockledge Dr., MSC 6612, Bethesda, MD 20892-6612, (301) 496-5717, Fax: (301) 402-3573, (866) 284-4107, ocpostoffice@niaid.nih.gov, http://www.niaid.nih.gov .

René A. Jackson, RN and David E. Newton, EdD

Disclaimer: This information is not a tool for self-diagnosis or a substitute for professional care.

Full Text: COPYRIGHT 2023 Gale, part of Cengage Group

Jackson, René A., and David E. Newton. “Infection Control.” The Gale Encyclopedia of Nursing and Allied Health, edited by Jacqueline L. Longe, 5th ed., vol. 4, Gale, 2023, pp. 1945-1948. Gale Health and Wellness, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX8506400626/HWRC?u=slnsw_public&sid=bookmark-HWRC&xid=b035ed75. Accessed 1 Aug. 2024.

-

RAT: Cellife COVID-19 NASAL SWAB TEST 680/CTN

RAT: Cellife COVID-19 NASAL SWAB TEST 680/CTN -

WIPES: Alcohol IPA 70%

WIPES: Alcohol IPA 70% -

Handicare Hand Sanitiser 12/CTN

Handicare Hand Sanitiser 12/CTN -

DISINFECTANTS: 5L Clinicare Hospital Grade IPA 70%

DISINFECTANTS: 5L Clinicare Hospital Grade IPA 70% -

WIPES: Clinicare Hospital Grade Disinfectant IPA 70%

WIPES: Clinicare Hospital Grade Disinfectant IPA 70% -

WIPES: Clinicare Alcohol Free

WIPES: Clinicare Alcohol Free -

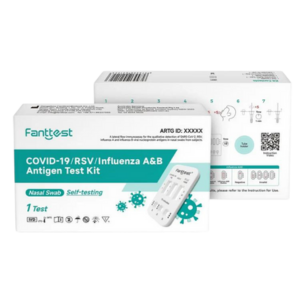

COVID-19 /RSV/Influenza A&B 4-in-1 Antigen Test Kit

COVID-19 /RSV/Influenza A&B 4-in-1 Antigen Test Kit -

DETMOLD Tri-Panel Respirator AGED CARE 300/CTN

DETMOLD Tri-Panel Respirator AGED CARE 300/CTN -

Instant Cold Packs

Instant Cold Packs -

JUSCHEK RAPID ANTIGEN SELF TEST NASAL 5T 500/CTN

JUSCHEK RAPID ANTIGEN SELF TEST NASAL 5T 500/CTN -

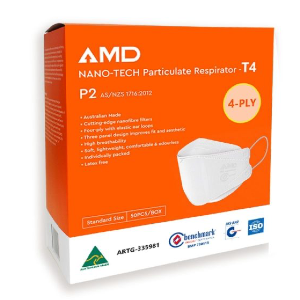

AMD P2 EarLoop Mask 1000 / CTN

AMD P2 EarLoop Mask 1000 / CTN -

RED Laundry Bags 200/Carton

RED Laundry Bags 200/Carton -

Nitrile Gloves / 2000 Carton

Nitrile Gloves / 2000 Carton -

30ml Medicine Cup – Graduated – 5000/CTN

30ml Medicine Cup – Graduated – 5000/CTN -

Cutan 400ml Foam Pump 12/CTN

Cutan 400ml Foam Pump 12/CTN -

Purple Cytotoxic Waste Bags 250 / CTN

Purple Cytotoxic Waste Bags 250 / CTN -

WIPES: Clinicare Hospital Disinfectant & Decontaminant

WIPES: Clinicare Hospital Disinfectant & Decontaminant -

NanoShield P2 Aged Care Respirator PREMIUM 400 CTN

NanoShield P2 Aged Care Respirator PREMIUM 400 CTN -

Vinyl CLEAR Gloves / 1000 Carton

Vinyl CLEAR Gloves / 1000 Carton -

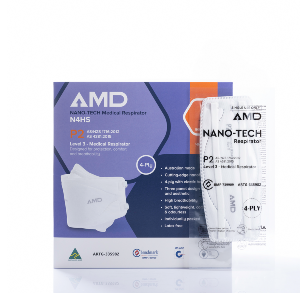

AMD P2 Medical Respirator 1000 / carton

AMD P2 Medical Respirator 1000 / carton